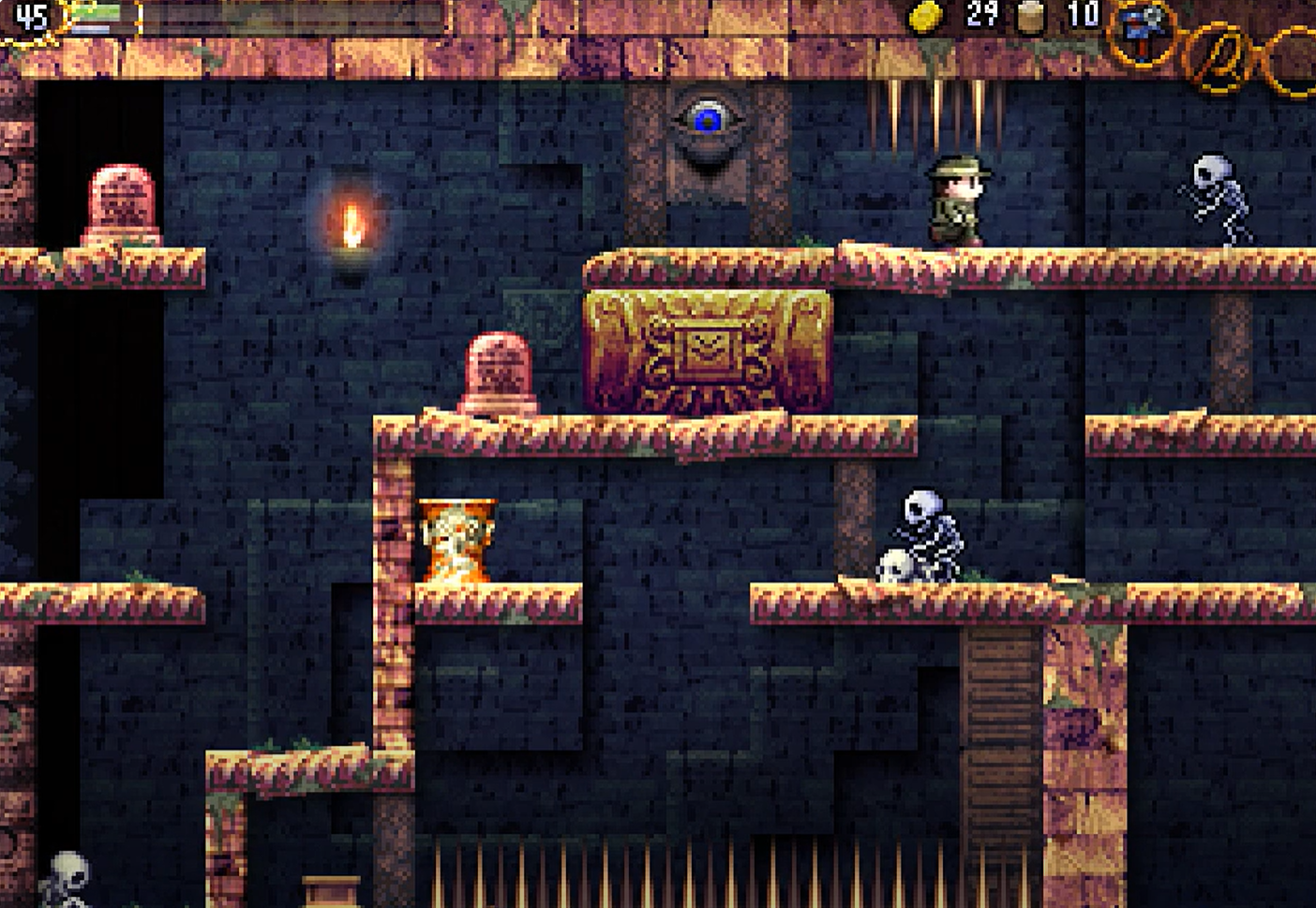

I'm one of those people who never shuts up about one specific video game, specifically GR3 Project's 2006 freeware metroidvania La-Mulana. This is surely due, in large part, to having seen Deceasedcrab's let's play of the game as a tiny, dumb child, and it thereby being my first exposure to those genres (both of video game and of video). Yet besides my own personal nostalgia, I maintain that the game is an extremely clever, atmospheric, and well-made example of its genre, and is one of the standouts of the early-mid 2000s indie scene. My feelings on the 2012 commercial remake are significantly more negative, for various reasons - some relevant to this piece, some not. The important part is, I regularly play through the game (as I would recommend you go do when you get a chance - it's on archive.org, though you might need to do a little bit of troubleshooting running it on modern computers due to its age).

It's a good game, yall.

It was on one of these playthroughs recently where, during the early areas I had long since mastered and memorized, I found my mind wandering to how they served as implicit introductions for concepts that would inform the rest of the game, without ever actually becoming a formal player-facing tutorial. It occurred to me, then, that this was the same thing the famous Tomb of the Serpent Kings does (or attempts to do) for tabletop roleplaying. And, much like La-Mulana, Tomb of the Serpent Kings has structural divisions within its text and paratext that form layers of instruction for play that build on each other.

So, y'know, since I've had a mildly original thought (a rare occasion), might as well write it down and see if anyone gets anything out of it.

The First Layer: the Enclosed Instruction Book

The most important thing I, or any other person recommending the original La-Mulana, would tell prospective players is to read the included manual. Not only does it provide the controls and some explanation of systems that might be mildly confusing - the basic mechanical levels on which you interact with the game - but it's also just a neat little feelie that plays into the game's two intertwined theses (the feeling of archaeological investigation, and the experience of gaming on the MSX computer system). There's even (minor spoiler) an important puzzle solution included somewhere in there, and other information you'll want to know or be able to reference.

And it comes with illustrations and lore and shit! It's charming!

The parallel is fairly obvious - the RPG equivalent to the manual is the actual rulebook of the game or system you'll be playing. Like the manual, it is not in and of itself the game - it doesn't contain the experience of play - but it introduces you to the game and the ways in which you'll play it, gives you a feeling of the game's atmosphere and tone, and encourages you to adopt mindsets that will be productive in approaching the game. And, much like the manual itself, you don't have to read straight through the whole rulebook of the TTRPG you're using (which can be a daunting prospect depending on the game!), but you can find the most relevant portions to understand what you'll be doing and how the procedures of mechanical play will work, the ways you'll be interacting with the game, and you can and probably should keep it on hand as a reference.The Second Layer: the 'Safe' Outer Area

When you start a new La-Mulana save file, immediately after a very brief introduction (literally 2 sentences), you're dumped right into the game's first area, the exterior of the ruins, the only direction or task you're given being that which you have from the manual (and your basic familiarity with, you know, the idea of a video game). You're here to find a marvelous treasure of some sort, but where and how you do that is up to you to figure out. So, you (most likely) start by checking out the door right next to you, receive very vague and cynical advice ('You can go into the ruins, if you'd like. You'll probably die like everyone else who's tried. Not that I care'), and are left to fend for yourself.Also, like, tangent, but the surface is just such a good example of how good the game is at establishing a mood with its seemingly simple graphics and its music. The darkness of the surrounding forest and cliffsides, with just a little bit of sky peeking through at the top, makes the village feel isolated and vaguely portentous, but the chipper and upbeat 'Mr. Explorer' gives a feeling of optimism and enthusiasm for adventure, its grandiose melodies hinting at the hopes of finding something incredible.

The surface - or its equivalent in Tomb of the Serpent Kings, the False Tomb - is a chance to apply and experiment with the things you learned from the manual. It's a simple area that gives you a few hints, a few goals to keep in mind as you move forward (gotta save up money to buy that software!), wide open spaces to move and jump in as you get used to the physics, and fairly simple enemies to kill and examples of the game's primary recurring simple elements (breakable pots with loot, signs to read, pedestals to activate mechanisms) to ease you into the act of playing the game. At the same time, it's not something you can completely and effortlessly clear out - there's danger, things you'll need to come back later to deal with, things (fairly clearly signposted) that will kill you quickly, a treasure chest you'll need to figure out how to open on your own. The set of interactions it gives you with the game world are limited, but it still expects you to take that world seriously, and teaches you that if you don't - if you try to fight the giant blue invincible guy with your leather whip, or jump unprepared into the rapids of the waterfall, or just bump into too many enemies without saving - you'll face genuine consequences, up to and including death.

The Third Layer: You'd Better Learn

If you live long enough to solve the simple not-really-puzzle at the entrance on the surface, then you're rewarded with passage into the thing the game is actually named after - the ruins of La-Mulana themself. This is where the game starts being serious, showing you the formula major areas throughout the game are going to have - solve puzzles, decode clues, eventually get the pieces you need to fight a boss - then beat it, hopefully. Also, much like Tomb of the Serpent Kings, La-Mulana seems almost to be going out of its way to teach you a specific lesson in each room.The lesson of this room is "Don't fall for obvious traps"!

In fact - and this might be a contrarian viewpoint - La-Mulana might do better on its room-by-room teaching style than TotSK. While it's discussed as a goal in the introduction, and maintained to a degree throughout, a lot of rooms don't actually have much of a lesson to them, or are lessons only specific to the dungeon itself (or even just a limited part of it), like the 'statues hide secrets' idea. In contrast, the things you learn in the Guidance Gate are going to be ideas you build upon throughout the course of the whole game. Still, the approach they have to these lessons is generally the same: you're never actually outright told anything, as a player. Instead, you learn the lessons from this area organically, in the course of play and doing the interactions with the world that seem either obvious or implied. You feel clever for figuring things out, even though the environment is designed to make you figure those things out.

Over-Tutorializing - Get Me Off Your Fucking Mailing List

I do not care for the remake of La-Mulana. I am very vocal about this. I am also, generally, alone in holding this opinion - the remake is far and away more popular, was the only version to get a sequel, and is usually considered a major improvement over the original. Certainly it's indisputable that on a technical level, the graphics and music are more detailed and impressive (though I have plenty to rant about on how the new graphics actually undermine the themes and atmosphere of the game). But what feels a lot less like an unqualified improvement is the changes to the way the game teaches you things early on.

Screenshot taken from raocow's playthrough, because like hell am I gonna download this version again.

In the remake, Elder Xelpud (fun fact: "La-Mulana", "Xelpud", and "Lemeza" (the main character's name) are all Japanese-language reversals/rearrangements of the developers' usernames - "Naramura", "Duplex" and "Samieru"), the character who told you to go off and die, takes a much more... active role, in the gameplay. He'll be sending you in-game emails throughout the course of play, and these things are - more or less - direct hints or instructions on how things in-game work. Now, figuring out how things work isn't a matter of going "Hm, the signs outside and the notes on these explorer skeletons are readable, but the stone tablets inside just display this weird cuneiform - I wonder if that's related to the Glyph Reader rom for sale in the village?", it's a matter of Xelpud emailing you the moment you see or interact with your first tablet and directly telling you "Hey, you need a Glyph Reader to read these."

This sounds like a minor quibble - and to a degree, it is - but it happens with everything early in the remake. Find a differently-shaped stone tablet and wonder what's up with it? You get an email saying "Hey, you can teleport to those with the Holy Grail." Solve a puzzle and pick up some shurikens? You get an email saying "You can find sub-weapons in the ruins, you use them with the sub-weapon button, they consume ammo that you can buy or find in pots." Fall into water and start losing HP? "Water hurts, you'll need to find an item to enter it without damage." You're not being trusted to figure out or intuit anything on your own, even the most basic things - so when the point comes that you're expected to do actual complex puzzles, rather than being confident in your ability to interpret or synthesize information yourself, you've been put in a mindset of expecting Xelpud to do it for you. You can, to be fair, unequip the email software if you really want - but how many players are going to think to do that on their first playthrough? Particularly when they can see there's an achievement for getting all of them? Oh - and progression is tied to reacting to these emails at one point (Xelpud gives you a clue that you won't get anywhere else), so you can't actually really do that anyway. The game, through this feature, is training you to be worse at playing it.

Ibid.

Other features in the remake teach you lessons that are deleterious to your experience, too. Whipping certain things in the ruins will cause you to get struck by lightning. It's painful, and sudden, and it can feel unfair at first, but after a while you start to get a handle on the rules behind it - essentially, things that trigger a lightning bolt are always going to be either 'sacred' objects of particular religious importance or major recurring features you need to deal with in other ways (aside from one really weird wall in the Mausoleum of the Giants that, as far as I know, is unrelated to anything). But evidently this was considered too harsh for Wiiware gamers, or beyond their capabilities - so the remake adds the Eye of Divine Retribution. See that blue eyeball up there? Now, in every single room of the game where attacking something can get you struck by lightning, that eye is there as a 'hint'... except the eye remains even if whatever can trigger the lightning disappears (which is a frequent occurrence!). Now, instead of the player learning a first-hand lesson to treat big holy relics with respect, the eye is teaching players to be cowardly, promising danger even when a player who had learned to develop their intuition in the original would realize there's none there. One of the very few improvements the sequel to the remake made (alongside making lots of things even worse) was make the eyes close once nothing in the room can trigger them.

There's one last thing for me to gripe about, and it feels really inexplicable. The original La-Mulana was a game that expected you to take notes, or else have a really prodigious and specific memory. There are specific numbers, rituals, orders, locations - all kinds of things - that you, the player, need to write down or remember. You can always go back to reread a clue - if you can find where it is. It demands a careful and detailed approach. The remake teaches you this skill doesn't matter, while at the same time demanding it more from you. Another piece of in-game software you can find lets you record the text (and diagrams) of any readable object or NPC dialogue, and reference it later indefinitely. The obvious message from this being a feature is "you don't need to make your own notes, this item will take care of that." Yet one of the few new puzzle elements the remake of this puzzle game introduces is one that demands note-taking - certain clue tablets are indecipherable, even with the Glyph Reader, until you've found an arbitrary number of rosettas stone in other later areas and backtracked to them. But because note-taking up until this point has become a process of just 'press button for screenshot', a new player isn't in a mindset to take their own notes on where they'll need to return to - so the point where you need the clues from these indecipherable tablets becomes an exercise in frustrated wandering through areas you've already explored.

What points or insights do I have here?

None. Goodbye! Play La-Mulana.

.jpg)

.jpg)