Between the table of contents and the spell descriptions themselves is a brief segment with rules on spell foci:

"Every mage must have some item or object through which he focuses the power of his magic. Some ideas:Staff or Wand

Crown

Sceptre

Packet of Herbs

Pointy Hat

Robes

Ring

Amulet or Talisman

Spell Book

Any other object agreeable to the player and the GM.

"In any case, the beginning mage must acquire or purchase his focal item before spellcasting. A beginner with one 1st level spell would then spend 1 day attuning his focal object to that spell: This is assumed to be done when a new expedition is outfitting.

"If a mage loses or damages his focal object, he may not cast any more spells until he gets a new one! Once the new focal object is obtained, the mage must spend one day per level of spell with each of his spells, attuning the staff to the spells, before he may use them."

This is quite flavorful, but I can see it also leaving the magic-user exceptionally vulnerable, since no special protective quality seems to be extended to the focus itself. A high-level mage who makes a daring escape from the jaws of death but fails to hang onto his hat would have to take many months off from adventuring or embark with an incomplete complement of spells.

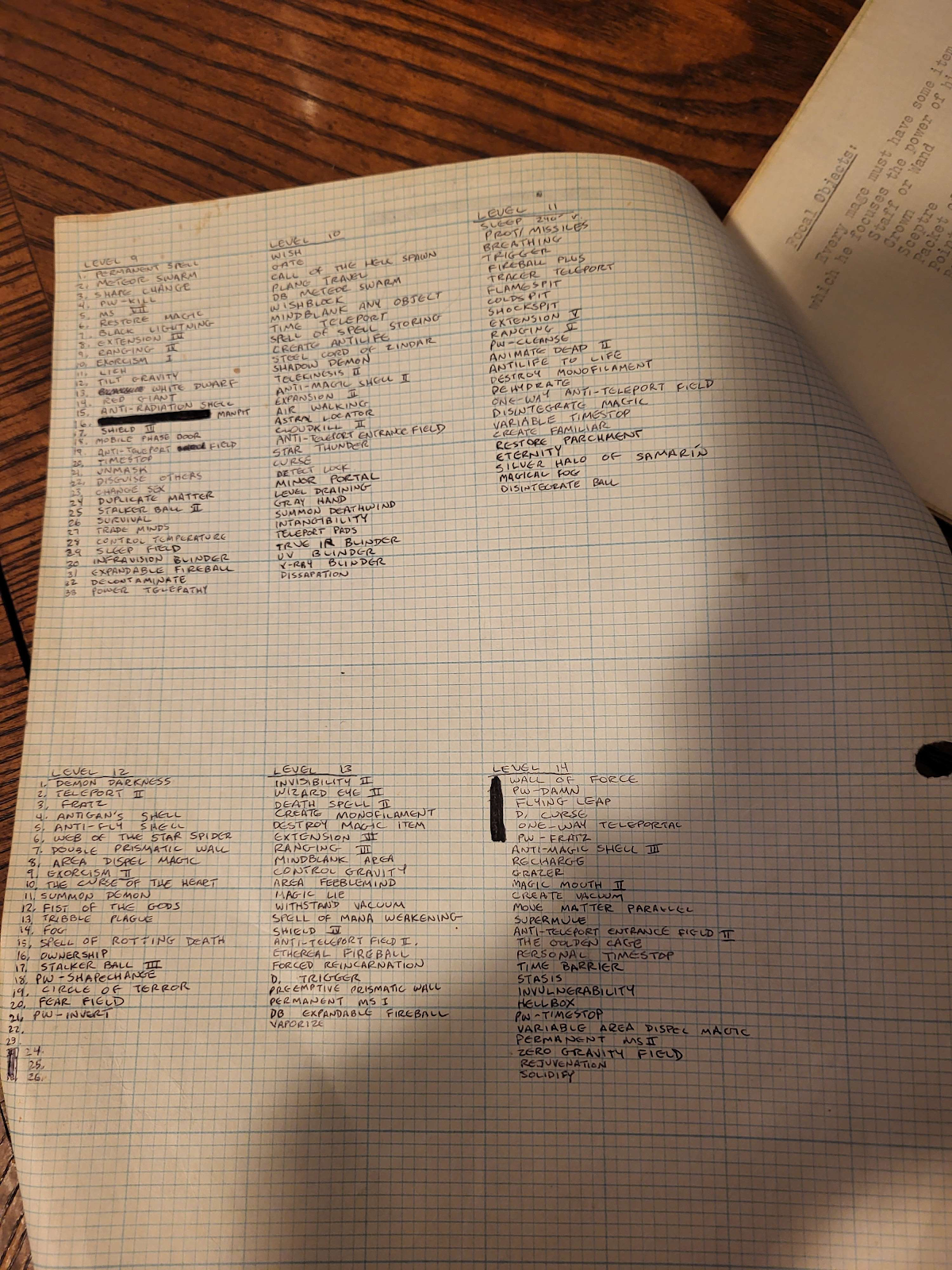

Spell descriptions themselves are given in two sections The first section is typed on blank paper (except for the 3rd-level spells, which are a longer but still incomplete list in the style of section two inserted at the appropriate point) and appears to consist largely or entirely of spells established from other sources, both the original OD&D books proper and the Arduin books. Towards the end of each spell level, handwriting inserts the names, but not descriptions, of the first few other spells appearing in the second section. Spells in section 1 are also numbered, except the third-level ones.

Spells of Level 1 are as follows - in places where a description has been redacted, the most legible or recent version is treated as canonical.

[Section 1]

1. Detect Magic: This spell determines if there is some enchantment laid on a person, place, or thing. It may only be cast on a single object at a time. If the item is magic, it will emit a soft blue glow. Range: 60'. Duration: 2 minutes. [P]

2. Hold Portal: A spell to hold shut a door, gate, lock etc. It will only work on non-living objects. A strong anti-magical creature will shatter a held door, and a "Knock" will open it. Duration: 2D6 2-minute turns. Range: 10'. [P]

3. Read Magic: This spell is necessary to read all scrolls written with Mages' spells. Without it, only the titles may be read. Range: 60'. Duration: 2 minutes. [P]

4. Read Languages: This spell makes any writing in any language legible to the mage casting it. Range: 60'. Duration: 10 minutes. [P]

5. Protection from Evil: This spell hedges the magic-user round with a magic shell six inches from his body. No enchanted monster may physically penetrate this shell. The mage also gains +1 saves and +1 Defense. This spell is not cumulative in effect with magic armor or rings. Range: Mage only. Duration: 1 hour. [P]

6. Light: A spell which lights a circle 30' in diameter. The light is not as bright as full daylight. Range: center up to 30' from Mage. Duration: 1 hour plus ten minutes times the level of the caster. [P X]

7. Sleep: Puts to sleep beings Σ HP ≤ Mage's level. Wake up if approached within 10'. Range = 240'.

8. Shield: By means of this spell the user imposes a moving magical barrier between himself and his enemies. It provides the equivalent of class 2 armor vs. missiles and class 4 armor vs. other attacks. Range: Adjacent to Mage. Duration: 30 minutes. [P]

9. Magic Missile: This is a conjured missile, fired with an accuracy of a composite bow +2, disregarding any dexterity bonuses. It does 1d6+1 points of damage, and there is no save if it hits. For every five levels above 1st which the mage has attained, he may fire an additional two missiles with every use of this spell. All of the missiles must be directed at the same target in the same melee round. Range: 150'.

10. Ventriloquism: The user may make his voice issue from whatever point within range is desired, without moving his lips. He may do this while he is carrying on another conversation, drinking water, etc. Range: 60'. Duration: 20 minutes. [P]

11. Darkness: A spell which causes total darkness in the area affected, making even infravision useless. It is otherwise the same as a "Light" spell. [P X]

12. Pyrotechnics: A multi-purpose spell which requires some form of fire to work. Does not work on living beings of any type. When employing this spell the Mage can create a great display of fiery, flashing lights and colors which resemble fireworks; or he can cause a great amount of smoke which will cover an area of not less than 20 cubic feet. The effects of this spell will depend on the source of the fire, and when the spell is over, the fire source is automatically extinguished. Duration: 20 minutes. Range: 240'.

13. Dispel Magic: The user may attempt to dispel the effects of any one encantation[sic] with this spell. The spell does not work on enchanted items of any type. The success of the spell is equal to the level of the caster of this spell over the level of the original spell caster. Range: 120'.

14. The Rosy Mist of Reason: A cloud of rose-colored mist which causes all intelligent beings within it to save vs. magic at -4 or be reasonable and discuss things instead of fighting. All unintelligent types have a 10% chance of leaving, a 20% chance of being indecisive, and a 70% chance of attacking. Range: 60'. Area affected: 60' diameter circle. Duration: 1 hour. [X] ([Margin note:] Semi: 70% discuss, 10% leave, 20% attack) [Editor's note: this spell is taken from Arduin 1, though with slightly different verbiage and the addition of the margin note.]

[Section 2]

Detect Shifting Walls & Rooms - Range = LOS Duration = 10 min. [P]

D. Sloping Passages, Stairs & Ramps - Range = 60'. Duration = 10 min. [P]

D. Secret Doors - Range = LOS Duration = 10 Min. [P]

D. Mechanical Traps - Range = 30' Duration = 10 min. [P]

Know North - Duration = 1 hour [P]

D. Food & Water - Range = LOS Duration = 10 min. [P]

D. Illusion - Range = LOS Duration = 10 min. [P]

D. Lycanthropy - One target. Range = 60'

D. Mutant - One target. Range = 60'.

Smokescreen - A screen of inky black smoke of the same dimensions as wall of thorns. 5% chance of blinding those who pass through for 1-20 minutes. Range = 120'. Duration = 10 minutes.

Create Frog - Creates a 1 HP, AC9 frog in the caster's hand. The frog lasts until killed.

Force Field - Caster only. Stops all natural attacks. Duration = 1 hour. [P]

Etherealness 0 - Caster only, puts caster on the Ethereal Plane. 10% chance/hour (noncumulative) of getting back.

Counting - Tells the mage the exact number of identical objects there are in a group of up to 100,000,000

Trapping Web - A gossamer webbing of fiberglass-appearing filaments, 10' D. It holds all of up to 6 H.D. Range = 30', Duration = 1 minute. [X]

D. Secret Panels - Detects secret panels, hollow compartments, and the like. Range = 60'. Duration = 10 min. [P]

Extinguish Small Fire - Gets one fire up to 10'x10'. Range = 120'.

Frost - A small (2' r) field doing 1DD of cold. No save. Range = 120'

Match - A small flame (1" long) on one's finger. Duration = as desired.

Wish - Infallible.

Heat - A small (2'r) field doing 1DD of fire damage. No save. Range = 120'

Cloak of Darkness - A form of invisibility vs infravision only. Not detected by see invisible etc. One target. Range = touch. Duration = 1 hour or until dispelled (dispels as invisibility).

Anti-Shadow - One target. Removes shadow completely. Range = touch. Duration = 1 day. [P]

Power Word - Zot! - Causes glowing purple letters saying "Zot!" 4' high to appear in the air and stay for 1 MR. May be cast in conjunction with any other spell. Range = 600'. [Editor's note: it has been proposed by various parties that this may be a reference to the newspaper comic strips B.C. and The Wizard of Id, the Adam West Batman television program's use of sound effects, or the 1947 novel Zotz or its 1962 motion picture adaptation, which concerns an individual with magical powers that are invoked via pointing and shouting the word 'Zotz'.]

Magic Trap - Enables a mage to store a L1-L3 spell in a container to hold his valuables. Both spells must be cast on the container. The MU must specify how to open the container safely.